[Editor’s note: this guest post was written by Alice Corble, after she attended the Taskforce sector forum. She describes how her different roles (as ‘Librarian - demonstrating value’ in Lewisham, as well as a Sociology PhD candidate at Goldsmiths) contributed to, and framed her participation in, the event.]

I attended the Libraries Deliver: Ambition sector forum in London at the Whitechapel Ideas Store in January and gained a range of valuable insights and connections from the day. The Ideas Store was literally buzzing with ideas as event participants and library users co-mingled in a complementary way, aided by excellent service from Ideas Store staff.

My reflections on the day are framed by my multiple standpoints, as a professional librarian, a social researcher, and as a member of the Libraries Taskforce Communications Sub-Group. In the latter role, my duties for the day included recording vox pop interviews with a range of attendees, capturing content in sessions, and contributing to social media coverage.

I participated in four workshops: ‘Designing libraries in the 21st century’ with David Lindley and Gemma John; ‘Evidence-based, long-term and sustainable planning’ with Ian Leete and Ben Lee; ‘Libraries core dataset’ with Charlotte Lane; and ‘Workforce Development’ with Alison Wheeler.

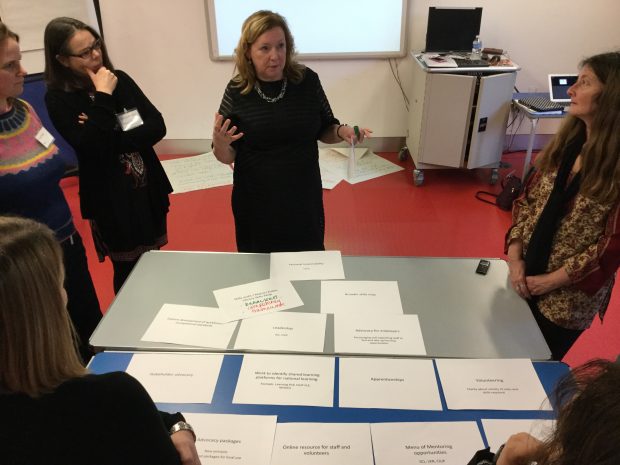

Alison Wheeler is the Chair of the Skills Strategy steering group, which is part of a CILIP/SCL joint initiative to create a Public Libraries Skills Strategy for public library staff. Alison’s workshop was a well-facilitated session that got participants arranging a pyramid of skills and training priorities needed to take public library staff into the future. The participants of the day were predominantly senior library professionals, portfolio holders and stakeholders, and this was reflected in the membership of the discussion groups for this session. While the session aimed at creating a hierarchy of importance for skills for front line teams, what was noticeably missing was representatives of front-line teams.

It is rare that front-line staff with the local perspectives get to have a voice in national discussions. My role with Lewisham Library and Information Service focuses on developing and communicating our evidence-base and advocacy, and the insight of the front-line team is a vital and critical element of this, so this prompted me to bring some front-line members of the Lewisham team along to the day. I was the only librarian to have done this.

One of the Lewisham staff who attended the data set and evidence base workshops, reflected that these discussions really opened her eyes to “just how little of what we do is actually captured – it’s all about issues and visitor figures, but that’s not even half the story of what we do, is it?” She went on to recount the wide range of service user needs that front-line staff meet every day, from assisting with navigating the increasing number of online forms and services mediating everyday life, to cultural events and reader development activities, none of which gets captured in the form of a data set or evidence that counts. Together we will be working on ways to address these gaps in our knowledge-base.

The senior library managers I spoke to on the day echoed similar concerns about how the impact and value of front-line team knowledge and practice is often missed in service evaluation protocols. One head of service argued:

“I don’t think libraries are very good at proving the case for the multiple impacts they have on, say, educational attainment, or economic development, or reducing social vulnerability, etc. Libraries are good things, but it’s not good enough to be a good thing; it’s about how you measure and improve the importance of the service.”

Another head of service made similar points, remarking on the myriad hidden things that happen in libraries, such as bringing different communities together by sharing one story in five different languages to address the diversity of the locality. She also pointed out:

“People keep saying libraries have to change, and yet history shows that since public libraries began, they have always changed and kept pace with changes in society… Too many people have a reified view of what libraries might be about.”

My own research findings agree with this point. The popular conception of libraries is indeed all too often a reified one, that is, an idea that gets set in stone rather than kept alive to reinterpretation. The library concept becomes reified when it is typecast as a dusty storehouse of books that doesn’t keep pace with the digital age. This preconception is most commonly held by those who have not actively used their libraries in a long time, and hence rely on the symbolic edifice of library meaning, rather than their lived realities as dynamic, evolving entities.

One of the biggest challenges in changing perceptions on libraries lies, therefore, in how to reach their non-users. I spoke to the Chair of the board of an independent public library mutual, who reflected:

“I think where there is a sort of mismatch with the Taskforce document, is to expect a transformation of attitudes and awareness, with no suggestion as to where the resources might be found to make that transformation. You’re not going to change attitudes and perceptions unless you find quite a surprising way of doing it.”

One way of doing this, he argued, could be to build strategic partnerships with social groupings not typically associated with libraries, such as sports clubs. While I agree there is value in this approach, it misses a vital component. This ‘surprising way’, I would argue, is held in the insights of the front-line teams. Front-line staff are vital resources, and although stretched thinly in these austere times, their voices and intelligence need to be heard and engaged with in ways that can open debate into less predictable directions, to create meaningful dialogue between theory, strategy, and practice to influence change from the bottom-up, both at local and national levels.

While the Libraries Taskforce and its members communicates through social media, blogs and events that are open to all, the primary means by which they liaise with each library service across the country is through heads of service.

We need to think creatively about ways to break through this hierarchy to make participation more inclusive and representative of the workforce. For example, when the Taskforce runs regional events, there could be designated communications roles for front-line staff in host and neighbouring libraries who are keen to develop their skills and experience in this area. This would offer a structured way for service managers to engage and embed library assistants and senior library assistants in conversation on local and national strategy and development. These opportunities could be supported by CILIP and SCL in their public library skills strategy.

As David Lindley shared with me following his engaging ‘Designing Libraries’ workshop:

“It’s absolutely vital that we communicate effectively with our own staff, especially in times of change. It’s the people on the front line who deliver the services and their value. It’s they who are in direct contact with the user. It’s they who are most likely to be affected by changes to delivery structures. They who are the advocates for the service. These are your sales people. They need to understand what they are selling.”

The Libraries Deliver: Ambition document sells the multiple impact benefits of the unique product that is the public library service, and unless the people delivering these services on the ground are invited and included in person to the processes that connect national strategies with local outputs, change will be ineffective.

With most public library staff lacking formal or professional qualifications, and training and CPD becoming the responsibility of individuals rather than organisations, I argue that it is the responsibility of leaders and managers to encourage front-line staff to attend national workshops such as these, to prevent strategies being shaped by top-down perspectives only.

As we all know, library services are much more than books and buildings; they are people too. And they would be nothing without the people who are the first points of contact for any library user walking through the door in search of support, inspiration or sanctuary.

------------------

Please note, this is a guest blog. Views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of DCMS or the Libraries Taskforce.

1 comment

Comment by Laura Swaffield, TLC posted on

This is interesting.

I would add that another insight is also missing - library users.

It's odd for any service or business to try to develop without getting input from its customers.

In the real world, where libraries are closing by the dozen or being dumped on to volunteers, it's local library users who are fighting for them, doing the research, making the case for libraries and for trained library staff.

In the real world, it's library users who have to voice staff concerns too, as staff dare not speak out.

In the real world, libraries have massive public support already.

To these people - and that's people all over the country as the damage becomes nationwide - the work of the Taskforce, alas, is completely irrelevant.

They'd love to discuss "surprising ways" - but they are desperately working 24/7 to try to ensure there's any remaining library service to have ideas about.

I understand why the Taskforce feels it must toe the line of its bosses the DCMS and the LGA. (It's less easy to understand why DCMS remains so passive...)

But the gap between aspiration and daily reality makes every good idea look a bit silly.

The Library Campaign has asked to be on the Taskforce steering group. That might be a start.